Written by Kerren Dieuveille

This past Sunday, September 1st, was Founder’s Day for the Historic Black Police Precinct Courthouse and Museum. I had the pleasure of sitting down with LaCriscia Fowlkes, the museum’s Archival Education Manager, to learn more about the history of the First Five, Founder’s Day, her job as an Archival Education Manager, and the museum.

Pictured: Kerren Dieuveille, Marketing Apprentice at Culture Shock Miami & LaCriscia Fowlkes, Archival Education Manager at the Historic Black Police Precinct Courthouse and Museum

1. What is the history of the Historic Black Police Precinct Courthouse and how did it eventually become a museum?

The building of the Black Police Precinct Courthouse was established in 1950 after the City of Miami hired Black officers, initially referred to as patrolmen, in 1944 during the era of Jim Crow, legal racial segregation, in the United States. The increase in the Black population in Miami post World War II led to a need for Black officers within Black communities. This idea was originally proposed by community leaders from historically Black neighborhoods, such as Overtown and Liberty City, because whenever White officers were dispatched to Black neighborhoods the result was that they either did not resolve the issue or made it worse, leading to fewer crimes being reported and by extension increased crime within those Black communities. Therefore, the officer and the precinct itself were created to cater to the need for Black officers from the community to address crime within Black communities.

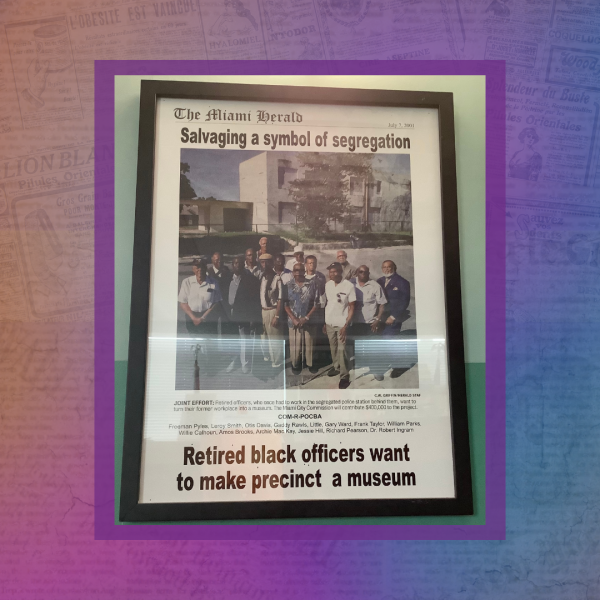

The Black Police Precinct Courthouse is also the only precinct that has holding cells, on the first floor, and a courthouse, on the second floor, in one building. The building closed on July 25, 1963 when the City of Miami built a new primarily White precinct during the time of integration. This made the Black Police Precinct Courthouse obsolete, despite the older precinct outperforming the newly built one. The building remained unoccupied until 2008 when the City was looking to tear it down. In response, local retired Black police officers traveled to Tallahassee to save the building which became a national historical landmark in 2015. The want to preserve the history of the building is what eventually led to it being made into a museum and education center for the neighborhood.

2. Who are the First Five and why is September an important anniversary for the museum?

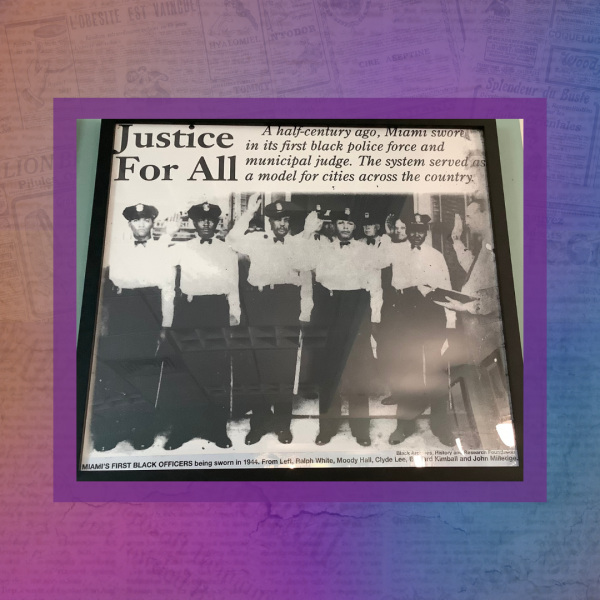

During the process of establishing a unit of Black officers, the City of Miami found fifteen upstanding men from the city of Overtown, then nicknamed “Colored Town”, to become trainees. The police trainees were trained at night in Brownsubs housing project ,then called the “Pork n Beans”, in Liberty City due to public pushback from White citizens within Miami. These fifteen men were trained by a number of individuals, including Captain James E. Scott, a Black WWI veteran and local community figure. The details of the training remain unclear, but the five men that successfully came out of that training were Ralph White, Moody Hall, Clyde Lee, Edward Kimball, and John Milledge who were dubbed “The First Five” and sworn in as patrolmen on September 1, 1944. At the time these patrolmen had no authority over Whites, job security, retirement benefits, or death benefits if they were killed in the line of duty.

This past September 1st marked 80 years since “The First Five” patrolmen were sworn in, and we acknowledge this with Founder’s Day. These men were significant because coming out of Jim Crow, legally enforced segregation through state and local laws, and the history of Klansmen in the Miami Police Department these patrolmen were a way for black neighborhoods to gain security from officers who came from the community and were more focused on community-based policing. Community-based policing is making sure communities have local officers who know the people in their neighborhoods and their patterns and struggles so they know who they can rely on for intel needed to keep the neighborhood safe because a relationship and trust have already been built with the community.

3. What does your role as an Archival Education Manager entail?

When LaCriscia Fowlkes first started her main focus was understanding how the information at the precinct is archived and what artifacts have been donated to the museum for preservation. Ms. Fowlkes also tries to ensure that the museum has enough information for individuals looking to do research and offers a space for those who have museum-quality artifacts within their families to donate or loan those items to.

Ms. Fowlkes has built upon the educational aspect of the museum by building curriculums that align with the temporary and permanent exhibits that can be utilized by local teachers. She also helps the museum offer neighborhood programming for people who are interested in history and policing.

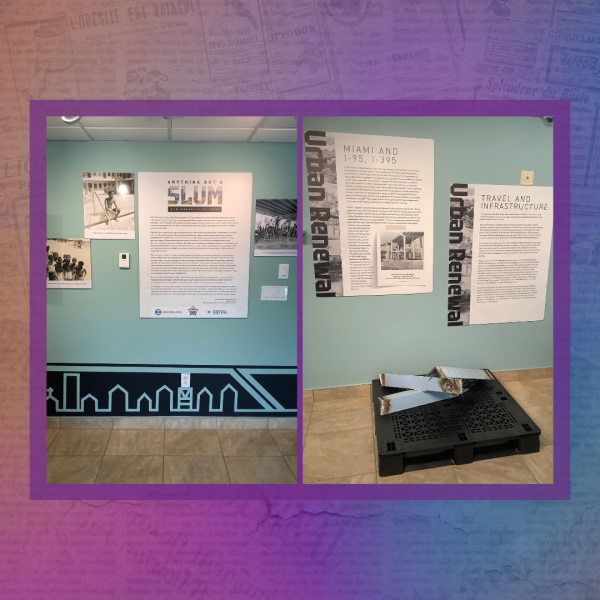

4. Can you tell me more about the current “Anything But a Slum: Miami-Overtown Before I-95/395” exhibit at the museum?

This exhibit shows the life and energy of Overtown before I-95/395 was introduced as part of the large-scale infrastructure changes that were happening throughout the US at that time. It shows how lively the Black Miami community was during Jim Crow and before I-95 took out a lot of the community resources and destroyed the revenue centers that used to be present in Overtown. Patrons visiting the exhibit can expect to see the heartbeat of Overtown, the history of hotels, and the former glory of the entertainment district of the “Harlem of the South.”

It also will help people examine how when divisive infrastructure was proposed in the 1960s nationwide it was often self-sustaining Black communities that were taken out bringing about a significant uproot of families to other areas of the County, the ramifications of which are still felt to this day.

5. How does the museum go about curating the items chosen to be put on display?

The items present in the museum’s permanent exhibition that are on display are from some of the most important steps taken in the early days of the precinct. That includes a section dedicated to Chief Clarence Dixon, who was the first Black person allowed to attend Miami’s formerly all white police academy in addition to serving as the first Black Chief of Police for a major American city. There is also the City of Miami Police Patch designed by Officer Robert B Ingram, which replaced the previous version and is the official seal still used by current City of Miami police officers.

6. What resources/community outreach programs does the museum have available to the general public?

- “Knowing the Law”: A part of their educational arm that helps the community understand laws coming from the government, how it affects their lives, and how to act with current officers serving their community

- Done through open conversations and meetings that happen at the museum

- Informational videos posted on their social media platforms

- Meetings held at the museum by Police Commander Katherine Baker of the City of Miami Police Department to hear from the community

- Partner with other organizations to hold meetings on gun violence and safety

- Sign up for the museum’s newsletter to stay informed and stay connected on social media

- Annual Interfaith Discussion: Done with Repair The World where participants celebrate going into sabbath with them and hold conversations about how we are as much the same as we are different

- Upcoming Events: Meditation Mondays at the museum that will be open to the public as well starting late September/early October

Ms. Fowlkes wants the community to feel like they are a resource for them to learn and talk about history as well as the current state of affairs in Miami and how they all learn to manage together.

7. What special events does the museum host throughout the year?

The museum offers extended hours during the following holidays/special events:

- Black History Month

- Juneteenth

- Annual Founder’s Day Celebration

- Soul Basel: A segment of Art Basel meant to highlight the works of local Black artists in Miami within the historically Black communities of Miami

- Art pieces from local Black artists will be on display at the museum during that time

- Upcoming exhibits planned for the activity room space throughout the year

- Partner with the Miami Women’s Club and Major Leroy Smith Girl Scout Troop #1877 for an annual Back to School Drive in August

- Author Conversations

- Give Miami Day

8.How can the local community get involved with the museum?

- Our history is created through our families:

- Share oral histories with the museum of the experience of living in Black Miami for their families

- Donate or loan items from officers who served either out of this precinct in the '60s or after such as pictures, newspaper clippings, police reports, and other memorabilia that show the significance of Black policing in Miami

- Come by the museum and share in the history and see the history of policing in black communities and the progression of policing in black communities in the current day

9. Is there anything else you wish to share during this interview?

“Everyone should come and learn of the history of Black Miami through the lens of community policing. Understanding how community policing still needs to be elevated in many ways to protect our families, and sons, and daughters. And join in the conversation and understand how your life plays into the history of where you live because the reality is most people who make history in that moment are just living their life.”

— LaCriscia Fowlkes, Archival Education Manager

Historic Black Police Precinct Courthouse and Museum

Pictured: LaCriscia Fowlkes, Archival Education Manager at the Historic Black Police Precinct Courthouse and Museum